Timothy J. Clark’s Poetic Realism

Click here to download the PDF reprint.

By Leo J. O’Donovan, S.J.

In the delicate, radiant medium of watercolor, light can be part of the scene itself, as in Winslow Homer’s paintings of fishermen in the Adirondacks or wind-tossed palm trees in the Bahamas. It can contrast the warmth of a woodland scene by John Singer Sargent with the magic of his Venetian Nocturnes. In Edward Hopper’s vision of isolation and loneliness in American life, light becomes integral at once to both the immediacy and the distance that throbs through the art. At the pinnacle of achievement, J.M.W. Turner’s enraptured love of light and atmosphere brought his watercolors almost to the dissolution of form. It was he who championed watercolor as a medium equal to oil painting.

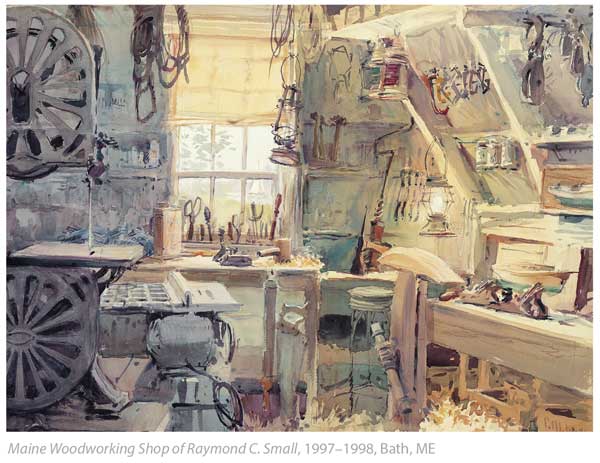

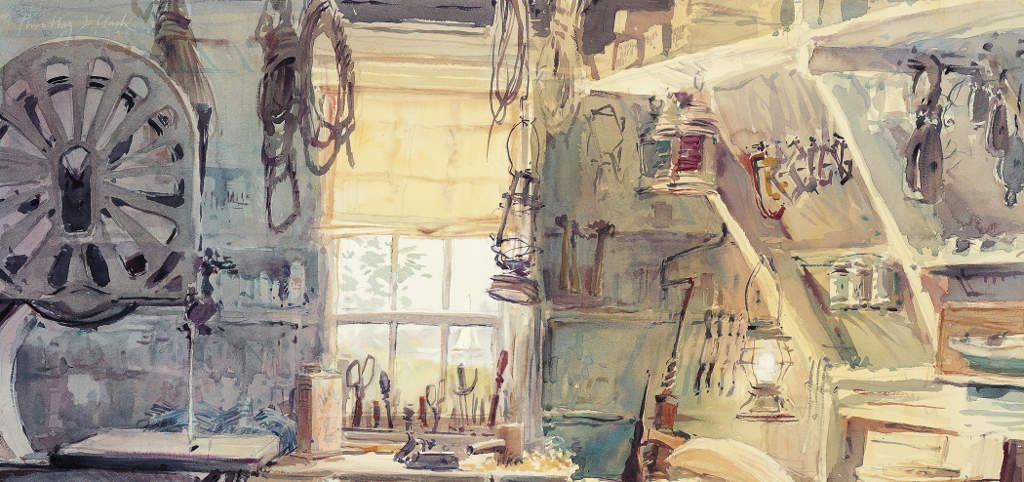

In the best work of our contemporary, Timothy J. Clark, light seems itself to create the scene before us—to reveal it not simply in the sense of showing it to us but in the deeper sense of actually bringing it into existence. We see the church nave, the craftsman’s workshop, the mystical moonscape as though it were just now appearing, a revelation in and of the moment.

This is what makes the light in Clark’s watercolor paintings sacred. It is given to us as a gift, a creative act beyond our comprehension. Each of the artists mentioned above—all of whom have influenced Clark deeply—are masters of light in various ways, taking us deeper into the world while dazzling us with their virtuosity. But Clark probes the creative act itself, the “otherness” it offers, the mystery of appearing (not mere appearance)—the sacred. In this respect he is indeed an heir to Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis and his metaphysics of light in the 12th century.

One of seven children, Timothy J. Clark was born in Santa Ana, Southern California, in 1951. At the age of nine he realized he was meant to be an artist and at 17 enrolled in the Art Center College of Design. In 1972, he was awarded a certificate in fine arts from Chouinard Art Institute and two years later a BFA from the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), which had been formed by the merger of Chouinard and the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music. He added an MFA from California State University, Long Beach, in 1978. But the degrees mattered less than instructors like Harold Kramer and Don Graham and, later, artist friends like Will Barnet, each of whom Clark—with characteristic warmth—recalls gratefully. Other major influences have been his annual trips to Europe (the first in 1982) and, above all, Marriott Small Kohl, whom he married in 1991 and with whom he shares homes in Capistrano Beach, CA, and West Bath, ME, as well as an apartment in New York City. After first painting with oil, he now works almost exclusively in watercolor—and is never satisfied if, at the end of a day, he hasn’t painted—a discipline that charges his oft-cited book Focus on Watercolor (1987).

The majority of the paintings in LUMA’s exhibition present interior and exterior views of churches Clark has visited with Marriott. “Searched out” might be more accurate. They take us from Northern France south to Languedoc and on to the Pyrenees; from Rome (especially) to New York and Chicago—in the very recent views of Madonna della Strada Chapel and Saint James Chapel. In each case, the light is proper to the terrain visited and its own distinctive palette. The showstopper is surely Nessun Dorma, an operatic tour de force that takes its title from Calaf’s third act aria in Puccini’s Turandot. The work combines a gleaming vision of Michelangelo’s peerless dome for St. Peter’s Basilica with a stunning Roman night sky, and the quite ordinary rooftops over which the painter saw the scene from the sixth floor of his hotel. He completed the painting on the night of the day when Benedict XVI resigned from the papacy

Visitors will notice how much Clark loves the domes of Baroque churches, as in Salute Impressions; Piazza del Popolo; and San Carlo al Corso Crepuscular, which could be a preparatory study for Nessun Dorma. More subtle is his ease at manipulating actual architecture to present a stronger sense of a church’s interior space. This is most notable in two extraordinary pieces—Cathedral Luminescence and Baroque Altar—in which windows large and small both flood a place of worship with light.

The atmosphere created by contrasting light and darkness is also essential to dreamlike nocturnes such as Moonlit Night and gritty urban scenes such as Sunday, Morning Steam. Clark’s New York scenes are slyly multivalent, confidently evoking the tradition of artists painting in their studios and about their studios, while also subtly evoking Teilhard de Chardin’s famous dictum “Everything that rises must converge.”

Clark’s evocative way with the human figure is evident in paintings such as Saint Nicholas Church; Rome Interior; and a sculptured Altar of Saint John Baptist de la Salle, Saint Patrick’s Cathedral. Each is a winning display of Clark’s compositional skills and mastery of occasional abstraction. Equally engaging are his still lifes: Summer Lemons; Dory Fleet Fresh Catch; and Table for Two, Pyrenees, in which the exquisite, brightly painted still-life on the table plays the violin to the cello of the empty, dark wood chairs. Who is coming? How will the dinner go? Or have they somehow been prevented?

Maine Woodworking Shop of Raymond C. Small is a kind of synthesis of all the work in the show—a workshop that is also a kind of studio and a sanctuary. It belonged to Marriott Clark’s father. All the workman’s tools—the auger and the adze, razor strap and mallet, wrenches, knives and chisels, the caulking mallet, and the band saw—are as if alive in the cool morning light of autumnal Maine. Seeing them we feel that they were used in imitation, whether acknowledged or not, of a creator who has wrought our world out of nothing but love and continues to create it still—towards a true and more just humanity—for which the beauty of work like Clark’s is a redeeming pledge.